What is a Proof of Concept?

In a journey to innovation or to a new, better-performing product – the first major step is to Proof the Conceptual feasibility of the original Idea. It should be relatively inexpensive and quick and cover burning questions and concerns that could be dealbreakers on the way to a successful outcome.

The proper definition of this fundamental step is often lost on cooperating parties – which brings misalignment in the expectations of what one should get as the result of a Proof of Concept.

Proof of Concept Definition

For an innovation, an upgraded product, or a completely new concept – everything starts with a Demand and an Idea of how to supply that demand.

During the ideation process eventually, the conceptual and theoretical alignments are reached – and there is nothing else left than getting to the practical implementation of this idea – This is when a Proof of Concept comes into play.

There is a variety of options to prove the feasibility through a PoC such as:

- Demo: a low budget incomplete and rough version of the end product.

- Animation: visualisation of the expected solution – as the solution is new, a visual representation can help with the decision-making of further development.

- Feasibility test reports: include diagrams, conclusions, and illustrations showcasing the answers of previously set questions that a PoC should address. This may not have a physical material as a result, but the conclusive proof of feasibility is rather valuable.

- Focus Group/Lead User: testing the custom audience interact with the product as a proof of idea, concept, and a way to gather new knowledge and insights for further development.

- Proof of the Tech: purely technical feasibility of the solution without need for a certain user interface.

- Mockup: non-functional prototype of an end product. This simply looks like the end product however it may have a different scale and no technical functionality.

Depending on the type of business, there are certain details a PoC should cover, however it is important to note that in nature, logic, and motivation – PoC is not meant to find commercial aspects of a business like the market demand for it, bring to a Minimum Viable Product (or even final Prototype), and neither to determine the best production process, although as a result of a PoC there is surely much more knowledge to base the financial decisions on as well (i.e., potential cost of production).

Instead, a PoC is there to validate certain aspects of a product/process/service, to make sure there are no deal-breaking obstacles on the way to implementing the idea.

This means that there should be a Proof of Concept definition between the teams involved, which should end up in a list of insights that generate confidence in the final product, or specific risks to tackle during development.

Therefore a Proof of Concept is an exploratory study, enabling informed decision-making toward the potential development of an idea toward a final solution.

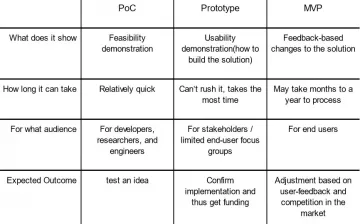

Proof of Concept vs Prototype vs MVP

A PoC is not a Prototype. This section of the blog could have ended here, however, let us further explore the ideological differences between the two.

In the development of innovation/product/service, the prototype (be it 1st prototype or final one) is an essential subject of work, it is the main practical step of getting an idea a feasible reality.

A prototype is a working model of the final solution with limited functionality. Once a prototype is ready, it goes through approval based on the potential possibility to become a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), and eventually be marketed.

Even though the goals of prototype and PoC are similar (development of an idea, identifying product’s potential and risks, etc.) – we can grasp their uniqueness by the “audience” they are meant for. Roughly speaking, A Proof of Concept is primarily meant for the technical and R&D audience – who will confirm a technical possibility If the solution (a feature of the product) can be developed; while a Prototype is meant for decision makers to understand How the solution will be developed, and have a complete global overview of all possible aspects of the operation (including financial, user experience, technical priorities in operation, etc.).

For reference, a Minimum Viable Product is the actual ready version of it, however it is a common understanding that even after complex PoC and Prototyping activities , there may be some polishing involved after the solution is out in the market – this is why the developers implement feedback-based change management once a product is out for a selected group of audience.

How to ensure a PoC is successful?

This might be stating the obvious, but after the Ideation process a Proof of Concept is going to happen either way during the development – sometimes it happens during the implementation of the idea by skipping the feasibility study, sometimes it works, and often it does not and the manufacturer finds out the defects of the idea once it is already in production. Examples of this are everywhere even with high-end products coming in faulty or sometimes even dangerous.

With this said, a Proof of Concept is successful, first and foremost when it is conducted before the real-life manufacturing of the products, and only then, it is as successful as the proper preparation and implementation of the said PoC.

Let’s prioritize and list the steps for successful PoC.

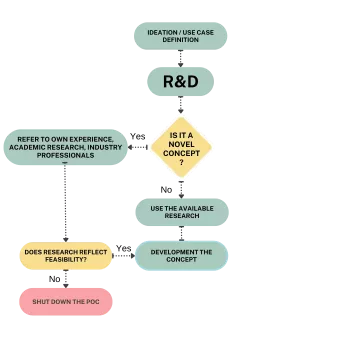

1. Research and Development

The history of similar work, the successful or faulty use cases analytics on what data already exists based on experience, published scholarly articles on these themes, interviews, and references from relevant professionals in the sector, and other activities to research as much on the topic as it is accessible and necessary. Often an R&D team is working on a project that has never been done before, thus there may be little to no references for them, in this case, the R&D team may rely on:

- Set prompt and relevant experiments to create the necessary knowledge of reference

- Their own professional reference in the field

In these cases, it may take longer to build up a PoC, however it becomes a bigger value too – as an exclusive finding and knowledge that can be shared with others in the industry.

2. Specification of the Demand of the Idea

Once the research around the topic is conducted it is important to know who will use the final product, why, in what environment, and gather as many details about a final use case as possible. At first, it may seem like this is a job for the innovation lead or a task coming from simply a business background – however, the answers to the aforementioned questions can drastically pivot the PoC as well as the rest of the development.

3. Is the Idea in Fact Feasible?

We have already found the need for technical feasibility, meaning if it is possible to implement the idea – however, it is not less important to understand the implementation feasibility of the idea

- Are there any third-party tools you will need to use for implementation?

- Is there an outsourced service to hire, and are there any equivalents if this service fails?

- Cost of implementation (manufacturing of parts, hardware and software alignments, staff and systems needed for maintenance and repair, etc.)

- Is the idea technically scalable?

Justification for Investment in PoC

For Internal management, not directly involved in innovation and R&D tasks – it may be difficult to quickly grasp the understanding of why a PoC is needed. And even for the R&D rep – why not have a clarification of practical decision-making reasons behind a PoC once and for all?

1.Understand the Issues In-depth

There is always speculative questioning involved in the ideation phase, with the notion of “what can go wrong?”. A Proof of Concept helps to detect the severity of these potential issues, the priority of addressing them in the future, the possibility of addressing them in the future at all, or if these issues are in fact non-existent.

2.Reduction of potential risks

As a PoC is a smaller project, dedicated to identifying potential feasibility – it gives an opportunity not only to know the potential risks but also to analyze the ways how to address them best. It is a unique stage of gathering knowledge, rather than delivering the final, identified product, thus researchers and innovators of a company shine here the most and bring the biggest return on the investment in their labor.

3.Usefulness and potential Success definition

A PoC helps to know in advance if a product can, in fact, be useful for a potential user, or if e.g. it will have to cost much more than expected in the ideation phase. This phase helps the manufacturer understand if the gap in the market can be met by the new product they are working on – or if it is time to stop the process before it is too late.

4.Spend on PoC and save on Time, Reputation and Expenses

Perhaps the most important advantage of a PoC and one of the largest motivations for a feasibility study is gathering certain security of potential large investments on time and financial resources, and keeping away from the sad reputation of a non-released product that “ate up” vast amounts of resources.

A PoC is meant to prove the functionality of a product or identify the battles that cannot be fought – this cannot be done in the ideation phase and it may be too late in the prototyping phase.

See the ideation phase results in a concept that is usually exciting and sparkles with potential – however, should you be deep in spending, and months of development – certain unsolvable issues may come up, proving the waste of the time of the teams involved in the work, the resources spent and thus the reputation is exposed to potential PR scandals.

What is our Experience with Proof of Concept?

Our own experience at RVmagnetics has shown that different corporate and business cultures from all over the world have their unique effects during these internal in-depth identifications of the issues. Sometimes a PoC result was expected to put the process on positive rails, and if any additional obstacle was discovered during the PoC – the project would be shut down, while in other cases the partners were glad and had an initial expectation do identify obstacles during PoCs, as it is the soonest point to do so and can be addressed right away (and only if the obstacles would not be possible to tackle, could the project be shut down).

There were also great learnings with strategic partners choosing to invest in two PoCs with opposite, competing logics for the same idea, to clearly identify the more relevant one (or possibly none) for a further development stage. Other partners preferred to strategically invest their R&D capital in PoCs that identified new, a potential solution for their further R&D plans activities, which they would later take over and start development rather promptly, as they already had the initial confidence of the technology from the previously-conducted PoC.

Eventually, we can conclude that it is better to invest in a quick and relatively inexpensive Proof of Concept and potentially be left without a final product than to invest in a long-term project and spend months/years, great expenses, and the important time of the personnel – and yet still, be left without a product.